Ocean Pacific Apparel Founder Jim Jenks Dies, Helped Birth Modern Surf Industry

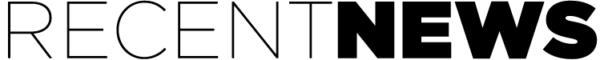

Jim Jenks, the former surf shop worker who turned Ocean Pacific into an industry-defining label that helped bring professional surfing to the U.S., died on Sunday. He was 83.

Jenks and his business partners created an apparel label that cleared several firsts for its time, acting as a bridge across the worlds of surf, fashion, art, and music. The brand grew to about $400 million in annual revenue from global licensing before the business was sold in a series of deals beginning in the ’90s. Jenks officially left Op in 1988, retaining the trademark for Newport Blue, an Op men’s line, and grew it to roughly $20 million before selling the business about five years ago.

Op’s reach – particularly of its corduroy walk shorts – and sheer size cleared the path for many more surf brands to eventually make their way into the market.

“He knew what he was doing; he was very sharp when it came to design,” said Walter Hoffman of Hoffman California Fabrics, which brought hand-dyed fabrics to the U.S. surfwear industry, including Op. “He was really good at designing and he was a pleasure to work with.”

Op, originally launched by John Smith, began as a surfboard brand in the 1960s and traded hands a couple of times before Jenks had the idea to launch apparel in 1972, obtaining the Op name from then-owner of the brand Don Hansen of Hansen’s Surf Shop.

Jenks’ contributions to the surf industry ultimately nabbed him a place in Huntington Beach’s Surfing Walk of Fame as a “Surf Culture” inductee in 2017.

“They wrote their own playbook there on the fly,” said Jenks’ son Jim Jenks Jr., known as Junior. “He was a hardcore surfer, motorcycle greaser, which in the ’70s, you weren’t. We were action sports before action sports knew what it was.”

Jim Jenks. Photo courtesy of SWOF.

Disrupting Apparel

The original ownership of Op’s apparel business was Jenks, Hansen, Robert F. Driver, and Chuck Buttner. Buttner first met Jenks at Montgomery Junior High School in San Diego’s Linda Vista neighborhood. The two kept in touch and when Jenks had the idea to start the apparel company, he contacted Buttner to join him.

“It was interesting,” Buttner said remembering the early days of Op. “I took care of the sales and he did design and production. It took a couple years to really get going. He was probably the best color person in the entire garment industry at the time, and he really loved the surf industry.”

Jenks and Buttner reached out to Gary Mykles in Op’s nascent days about getting into the knit shirt business. Mykles promised he could sell a million shirts in a year. He hit that target in about eight months and stayed with Op for over a decade, working his way up from a sales rep to regional manager and then national sales manager.

“We had a nice little place in San Juan Capistrano where we could hold our sales meetings on the green couch in the warehouse,” Mykles remembered. “We used local contractors around there and just started building off of that.”

It wasn’t long before the brand got traction and the company struggled to keep up with demand.

“At one time in my office, I had a map with a black line drawn across the middle of the United States and it said don’t go above the black line because our increases with our current account base were so great, we couldn’t finance more growth,” Mykles said. “We gradually opened the Northeast, Midwest, Southwest, Southeast. We introduced the active surf style everywhere in the country and pioneered that business. Then all the other companies started chasing us – the Katins, the Hang Tens. But Jim had that creative touch and when they said it’s time for T-shirts – the T-shirt business was non-existent at the time – we went out and peddled them.”

Op began licensing in the early ’80s, a move that further accelerated its ballooning footprint.

“During the infancy of Ocean Pacific, the big competitor was Hang Ten and so through the infant years that’s who we were compared against,” Buttner said. “As the years passed on, a company called Quiksilver and then Billabong presented themselves.”

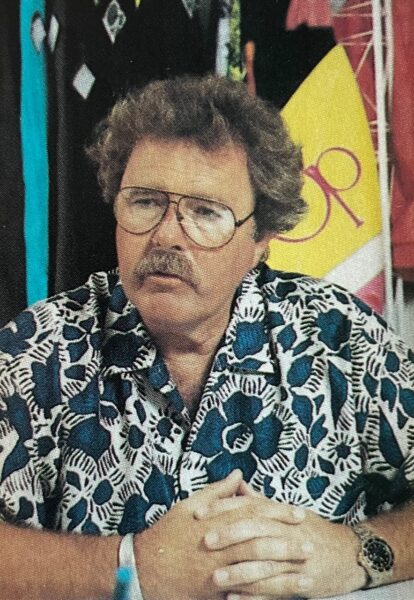

An old Op advertisement for the company’s shorts. Photo courtesy of the SWOF.

The Iconic Cord Short

One would be hard-pressed to find someone who grew up in the ’70s or ’80s who wasn’t familiar with the Op name and the company’s famous corduroy shorts.

“If you were a kid in the country, you wore Op cord shorts and when it was too cold for that, you wore a pair of Levi’s 501s or 505s. That was the dress code,” Mykles said. “It was a style that Jim put together. Every construction worker, every painter, every kid wore that short. People said, ‘Oh, you can’t sell that thing in this humidity and this hot climate.’ And we sold them.”

The Op cord short was what Allan Seymour, who previously handled Op special events and the surf team, called a “ticket to a whole other lifestyle universe for everyone.”

The practicality of the short for surfers couldn’t be beat, but it transcended the core surf industry.

“All of a sudden, you had people in Kansas wearing Op shorts and Aloha shirts, and the guys that were water skiers or going to the lake were wearing Op trunks because they were so functional. They hit the market perfect with that short,” Seymour said. “Before Quiksilver, before Vans, before everything, Op was the first one to really be big.”

Some in the industry today give credit to Op for paving the way for the modern surf industry.

“It was the product. They had more product and they expanded into sweaters and jackets and women’s and kids. No other surf brand did that,” said Greg Garrett, who worked at Op in the ’70s before moving on to Gotcha and then Z Supply. “Look at all the people that started at Op. My God, it’s endless. There probably wouldn’t be a Z Supply or Gotcha if it wasn’t for Op.”

It helped that Jenks and the rest of the management team created a culture of fun that made a lasting impact on many employees, starting with his son Junior who began working in the warehouse at age 16.

Jim Kempton, Don Hansen, and Jim Jenks at the Op Pro 40th anniversary event in 2022. Photo courtesy of Junior Jenks.

“Number one (lesson) was having fun because he definitely had fun,” Junior said. “It was such a small industry back then that we helped everybody. When we were successful, Quiksilver was successful and Billabong and everyone else. That was the one thing my dad really wanted to do was grow an industry and he was an early part of that.”

“I took everything with me,” Garrett said of the learnings from that time. “Op was the best company I ever worked for. That’s a fact. It was the way everybody was, the people. It was a real family.”

Nina Vance, the former Op national promotions director in the late ’70s, echoed the sentiment. Vance was working at a chocolate store when Buttner walked in, the two struck up a conversation, and Buttner attempted for about a month to woo Vance to work at Op.

“It was the best job I ever had,” Vance said. “The company was amazing to work for and it was so fun. We were one big family and I don’t think I’ve ever worked for a company ever again with that type of atmosphere. The camaraderie there was wonderful and it stemmed from Jim and Chuck.”

She remembers being awarded a gold Op necklace, something typically gifted to those in sales for exceeding $1 million, while she was at the company.

Peter Townend, Jim Jenks, Chuck Allen, and Ian Cairns. Photo courtesy of SWOF.

Changing Surf

The start of the Op Pro was among the major highlights of Vance’s career, which she credited the company for helping to jump-start.

The first Op Pro, held in 1982, drew more than 50,000 people to Huntington Beach, bringing with it instant scoring and the introduction of the priority rule.

“Jim was critical to the development of professional surfing in America,” said championship surfer Peter Townend. “A lot of people didn’t know that. Everyone thinks of Op as a clothing brand, but it influenced surfing.”

The Op Pro’s 40th anniversary, which was last year, is currently celebrated in an exhibit at the Huntington Beach International Surfing Museum.

Jenks hired Townend and Ian Cairns’ Sports and Media Services to produce the event, which marked the first International Professional Surfers World Tour contest in California. The Op Pro also served as the precursor to the U.S. Open of Surfing.

“One of the great things about Jim was he was a happy-go-lucky guy and Op became famous for its legendary parties,” Townend recalled.

Those gatherings weren’t open to the general public and were typically hosted for retailers.

Peter Townend, Jim Jenks, and Don MacAllister during Jenks’ induction into the Surfing Walk of Fame in 2017.

Big Personality

In fact, Townend recalled one memorable party when Jenks invited a whole circus inside a building along Interstate 5, where the Citadel Outlets currently sit.

“Full-grown elephants inside the building. It was crazy,” Townend remembered. “Jim Jenks was the mastermind of all that.”

Junior Jenks, Mitchell Jenks, Jim Jenks Sr., Matthew Jenks, and Mike Jenks – Photo courtesy of Junior Jenks

Long-time friends and former colleagues remembered Jenks’ 90-foot yacht with a 30-foot sport fishing boat riding on the back on shocks.

“Jim was one of those guys who came from a meager background and was a true self-made man,” Seymour said. “He was very, very generous and helped a lot of people not only financially, but in their life. When they needed help, Jim was there.”

Hoffman of Hoffman California Fabrics remembered a plaque over the door of one of the rooms on Jenks’ yacht that was dedicated to Hoffman Fabrics.

“I gave him so much fabric and he bought so much fabric, he put our name on one of the staterooms,” Hoffman said.

Jenks was buying open stock fabric from Hoffman on credit when he first began designing Op tops, which were originally silky, Hawaiian-style shirts. Once the company began growing, the two worked together on custom textiles and continued a friendship beyond the business up to today.

“He was great,” Hoffman said. “Just a happy guy. He was always up. He was never a down person.”

Jenks is survived by his wife, Marilyn Jenks; his sons Junior and Michael Jenks; daughters-in-law Lori Jenks and Kerri Jenks; sister Jean Taylor and half-sister Stacey Jenks; and grandchildren Matthew Jenks, Mitchell Jenks, Meredith Jenks, Stephanie Jenks, and Debbie Kathol.

A celebration of life is being planned by the family.

“We will definitely have one hell of a party when we do it,” Junior said.

Junior Jenks can be reached at Jrjenks914@gmail.com.

Mike Jenks can be reached at Mike@nctcusa.com.

Junior Jenks put flowers on his father’s Surfing Walk of Fame monument after his passing – Photo courtesy of the Jenks family